“Human beings expend staggering amounts of time and resources on creating and experiencing art and entertainment — music, dancing, and static visual arts,” writes scholar Denis Dutton, a professor at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. “Of all of the arts, however, it is the category of fictional story-telling that across the globe today is the most intense focus of what amounts to a virtual human addiction.” Why?

The love of fiction is universal, Dutton writes, whether it is in the form of literature on the page, plays performed on stage, or as most evident in American anyway, dramas on television and film (the average Briton spends 6 percent of her entire life consuming fictions; I would bet the figure is twice that in America). The reasons for such conditions are lost in pre-history, writes Dutton, but we can gain much from looking at it through evolutionary perspectives.

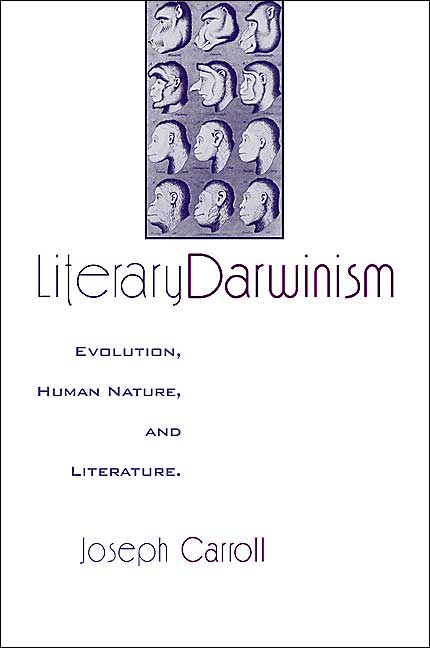

Where did this seemingly universal human taste for dramas come from? Was there anything in our past that made it advantageous to acquire and develop such a capacity for imagined narrative? It’s a fascinating line of thinking. Dutton reviews a collection of essays written by the expert in the field: Joseph Caroll’s Literary Darwinism: Evolution, Human Nature and Literature.

Before heading down this road of thinking, Carroll wants it understood that there must be some basics in place, writes Dutton. First, one must have the proper understanding of literature as much as an understanding of psychology. One must also have a perspective that human development begins and evolves through a set of “behavioral systems” — that the concept of inclusive fitness, as Dutton puts it, is the mover of all adaptations.

These seven behavior systems are survival, technology, mating, kin, parenting, social and cognition. The development of narratives and story may have played an important part in allowing humans to develop and evolve in each one of these systems. Consequences of such emotional development, both on an individual and group level, can be read in a book I just finished: The First Idea.

Dutton asserts that much of what has occupied evolutionary psychology theorists has involved mating and courtship. But much that has affected human history and survival involves more than mate selection.

“Much of what has taken human attention in evolutionary history is directed at bodily survival and at social maintenance: keeping yourself and your family well-fed and healthy, defending family and tribe, and making the tribe a stronger, more fit social unit.,†Dutton writes. “Inclusive fitness toward successful reproduction is the ultimate goal, but the lived fabric of daily human life brings many other purposes and ideas into play. Issues of social dissonance and cohesion, death and its meaning, as well as the challenges and adventures of youth that do not involve courtship, can also be expected to figure into the cognitive content of stories and art.â€